The Prized, Desirable Sight: The Meaning of the Moon Landing 50 Years Later

Far above, in the hush of the night sky, the earth whirled about in blueness. Over the lip of the horizon, the blazing lunar sunrise lit crags and craters, casting long shadows. The ashy architecture of the moon was like the austere limestone of a cathedral transposed into the cold cosmos.

In the earliest Christian churches of Rome the altars were placed on the western side of the sanctuary. The priest faced east to greet the rising sun as it came through the building’s front doors. He would lift the bread and wine and say the prayers of consecration, and, according to Christian belief, the Sun of Justice—God himself—would descend onto the offering.

On this July morning, a young man watched the light of that same star flood through the window as it came up over the lunar horizon. Bowing his head in prayer, he took the bread and wine in his hands, stared a moment as the wine curled and swayed mysteriously under the moon’s gentle gravity and, giving thanks, drank and ate.

Radioing to Earth, he said: "I would like to request a few moments of silence … and to invite each person listening in, wherever and whomever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way."

***

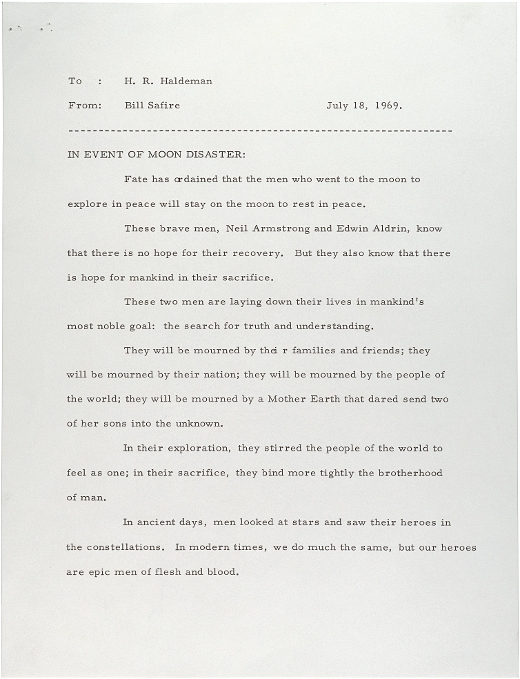

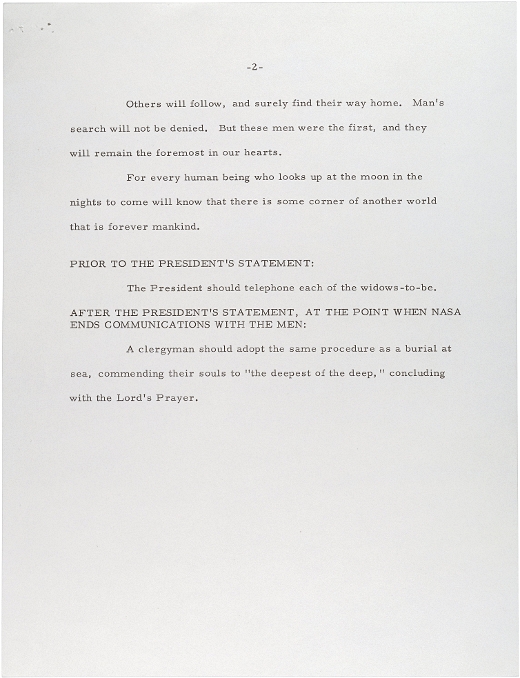

In the event Apollo 11 failed, President Richard Nixon was to address the country with the speech above.

What were the events of those hours, and what did they mean? In terms of material well-being, surely developments in agriculture, transportation, manufacturing, and other technologies were more significant. In terms of moral grandeur, the elimination of slavery and the dismantling of arbitrary castes and aristocracies were surely finer things. But there is something wondrous about those events of July 1969. The flight of Apollo 11 means more than its material description can indicate. It has a profound spiritual significance. It is a glorious echo of the impulse that drove ancient spiritual seekers to go after God in the mountains. As Abraham sought God in Moriah, so we sought Him on the moon.

There is a sense in which the whole endeavor can be called a miracle. Not that it was something supernatural, but ‘miraculum’ just means ‘wonder’, and that’s what the Apollo 11 flight was. There were thousands of things that could have gone wrong, a million tiny errors that could have sunk the mission and killed the crew. NASA didn’t even know how the materials of the moon’s surface would behave in the presence of oxygen and believed there was a chance that it might simply combust when it was brought aboard the lunar module; no one knew for sure how the human body would react to the lower gravity; scientists worried that mysterious moon-borne pathogens might make the astronauts ill. Can we imagine the delicacy of the calculations and maneuvers that could bring the lunar module and the command module to meet one another dock perfectly in space? Any error here would have been catastrophic. A few short decades ago men had taken their first stuttering flight off Kitty Hawk in a little craft of canvas and wood, now they were flinging themselves into the void.

C.S. Lewis, so often a perceptive observer of events, predicted wrongly the outcome of the moonshot. Rather than destroying forever the moon of poetry and romance, as Lewis feared, the Apollo 11 mission’s greatest gift to us was wonder. Who has not felt deeply stirred at the sight of the little blue Earth photographed from the lunar surface? I wish that Lewis could watch the faces of children at the Air and Space museum in Washington, as their wide-eyed gaze lingers over the Saturn V rocket or a space suit. Sentiment and fantasy fade with intimacy, but poetry and love thrive on closeness, which, paradoxically, always reveals deeper mystery.

The exploration of space fills even the skeptical with a religious awe. The perspective of human smallness, of universal bigness, pries an abrupt crack in the mundanity of daily life. It shakes us with that combination of trembling fear and exaltation that the Romantics called ‘the sublime’. Buzz Aldrin’s quiet communion ceremony, celebrated in the Presbyterian way, was an echo of his forebears in outer space; the crew of Apollo 8 read the opening chapters of the book of Genesis to the people of Earth as they watched the lunar dawn on Christmas day.

It’s possible, when encountering the cosmic vastness, to feel oneself to be so small as to be insignificant—to be an accident. But the testament of history, art, literature, and poetry points to another possibility: that the expanse of the evening sky can bring us to the feeling, not of arbitrary chance, but of some divine purpose too huge for us to get ahold of: someone greater than I made that sky, and, more strange still, made it somehow for me.

Something like this feeling lies behind the Greek and Norse myths from which we take the names of our constellations and behind the celestial stories of American Indian traditions. It also lies behind the constant cosmic images that shape the Abrahamic faiths. As long as human beings have been looking up, they have been confronted with the fundamental and final questions about life in the world. Most often, these reflections have ended in submission to the mysterious God, Gitche Manitou, the One whose personality echoes among the flaming orbs and through the gigantic halls of blackness.

Americans, perhaps, were particularly ready to embrace this ancient urge in the face of a competing world power that explicitly rejected the life of the spirit and the notion of the loving, creator God. Space travel may have been, for both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., about asserting some kind of dominance on the world stage. But Gene Kranz, the mission director of the Apollo missions, was not alone when he wept at the reading of scripture. It seems clear that, for many in this country, the moon landing had a meaning greater than the political machinations of the hour. Indeed, now it is an accomplishment shared and loved by the whole world.

And surely we feel this too; surely the effort of Apollo 11 makes us feel like a family with our species. Who are we? We are human beings, we are the explorers, the darers, the adventurers; we are the ones who, with dogged determination, throw ourselves across oceans, over mountains, and into the stars. We are the knowers and the lovers of the cosmos, the poets of the universe, the priests of Creation. There’s a brotherhood in this.

The Apollo 11 mission draws our hearts together, and then draws us higher. The human being, it has been said, is a meaning-seeking animal. The exploration of space is a search after meaning. It is an act of faith that the universe makes some kind of sense, that it is beautiful, and that it is worth knowing. And if this is true, we might reason, it is only because the fundamental ground of reality is a meaningful, purposeful, beautiful one.

***

Whatever we might conclude about questions of faith, it remains the case that contemplating the heavens draws us away from the petty squabbles of the hour toward more deep and abiding questions. In our day, so much of life seems to be occupied by the horizontal, by fretting about things on our own level. We look to the left and to the right to cast blame on our neighbors, we look behind to the past in bitterness and resentment, and we look forward to the future in the hopes of material comfort, wealth, and pleasure. But perhaps our happiness lies elsewhere than this lateral plane. That is the true meaning of the moonshot. The flight of Apollo 11 filled the eyes of onlookers with joyful tears only because, for once, they had remembered to look up.

Nathan Beacom is a writer living in Washington, D.C. His work has been featured in America Magazine, The Des Moines Register, and Commentary Magazine.